Why India’s Economy Is at the Head of the Pack

India is growing faster than any other economy in the world. This is not just because oil prices have fallen, writes CFR’s Sebastian Mallaby.

February 10, 2016 10:17 am (EST)

- Expert Brief

- CFR scholars provide expert analysis and commentary on international issues.

Not long ago, India was the laggard among the big emerging economies. In 2012, a giant electricity failure across the north of the country plunged millions into darkness, demonstrating the decrepitude of Indian infrastructure and the incompetence of public-sector management. The government had failed to create the basic props of a functioning economy: Kolkata’s main railway station, built in 1905 with fifteen platforms, had just twenty-three platforms—even though the number of passengers had multiplied one-hundred-fold.* Indian truck drivers spent less than 40 percent of their time actually driving; the rest was spent at tax checkpoints at state borders and in endless lines at toll booths. Small wonder that India’s growth lagged China’s—and Brazil’s and Russia’s. In 2013 Jim O’Neill, the Goldman Sachs economist who coined the BRIC acronym, demanded of India: “What is the matter with you guys?”

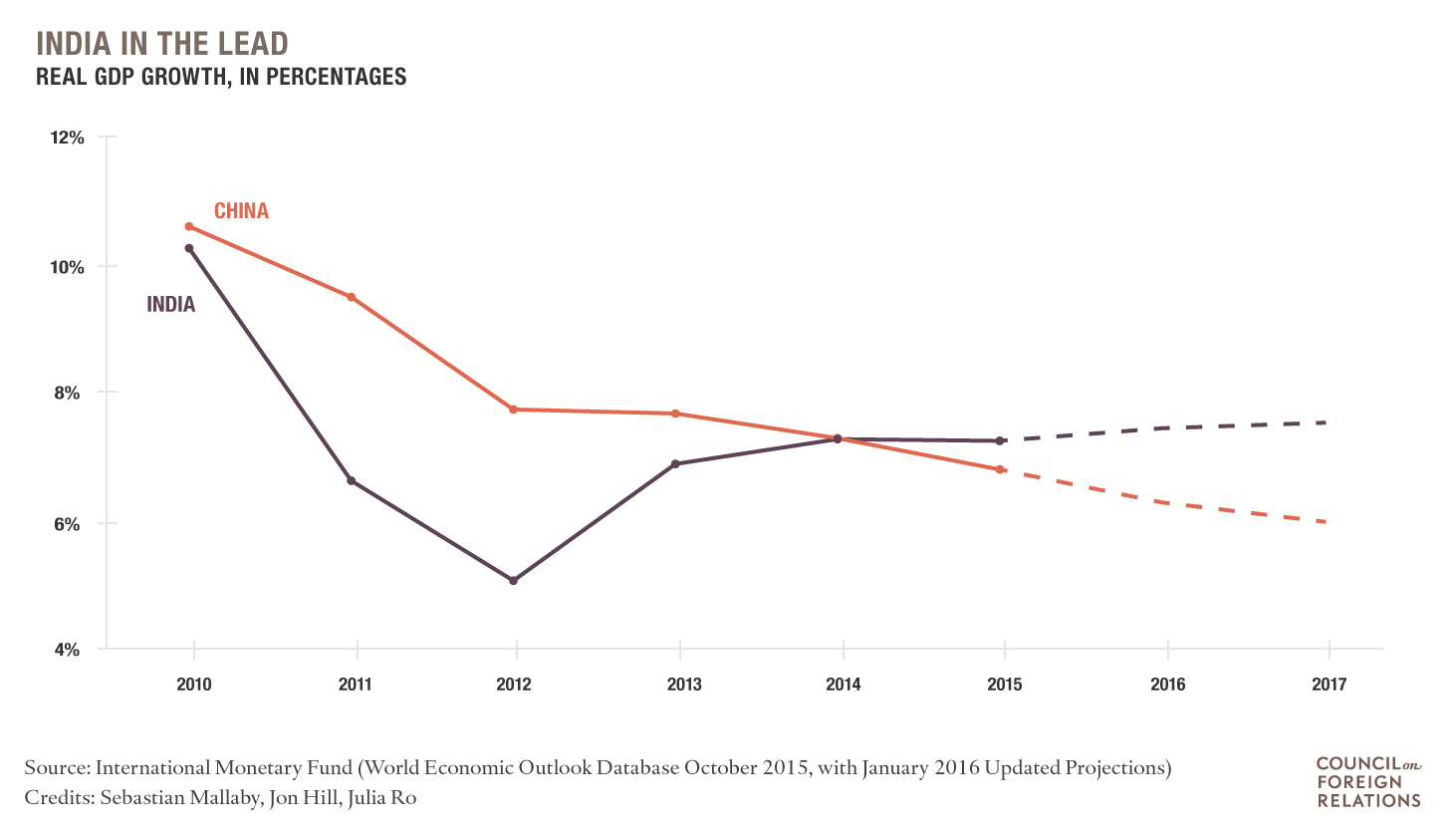

Three years on, India is resurgent. In 2015 its economy grew by 7.2 percent, faster than any other major nation. The travails of other emerging markets make this performance especially eye-catching: Russia and Brazil both shrank by more than 3 percent last year. Even China, long the world’s growth leader, slipped behind India, growing at 6.9 percent. And in 2016 India is likely to hold its position at the top of the table. While China began January with a bout of confidence-sapping market turmoil, India is expected to grow at the same rate as last year—or possibly faster.

Sustainable Growth?

More on:

The question is whether India’s resurgence can be sustained into the future, and the answer will matter not just for the prospects of India’s 1.3 billion people, but also for the balance of power in Asia and beyond. Some global companies seem bullish: General Motors and Foxconn have announced major investment drives in India; Apple recently announced plans to open its first retail outlet in the country.

But many thoughtful Indians are skeptical. They dismiss stronger growth, lower inflation, and a smaller government deficit as the lucky consequence of the fall in crude oil prices. They note that India’s banks are hobbled with bad debts, and that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s reform program is stalling. They joke that India’s prospects look brighter the farther away you are.

To understand the right balance between optimism and caution, begin with the effect from cheaper oil. As a big net importer of energy, India has seen its import bill fall by perhaps $7.5 billion monthly as global oil prices have tumbled from $100 per barrel to the low thirties. The windfall has made room for more spending on domestically produced goods and services, thereby stimulating growth. But this stroke of luck has been balanced by bad luck elsewhere.

Two lousy monsoons have damaged India’s large farm sector. Economic trouble abroad, notably in the Gulf petro-states, has hurt Indian exports and remittances from Indian migrant workers. And although foreign direct investment is up, skittish global investors withdrew capital from India’s stock market last year. Taking these factors together, the country’s growth cannot be dismissed as the product of ephemeral good fortune. Rather, it reflects something more solid: a marked improvement in the quality of India’s macroeconomic management.

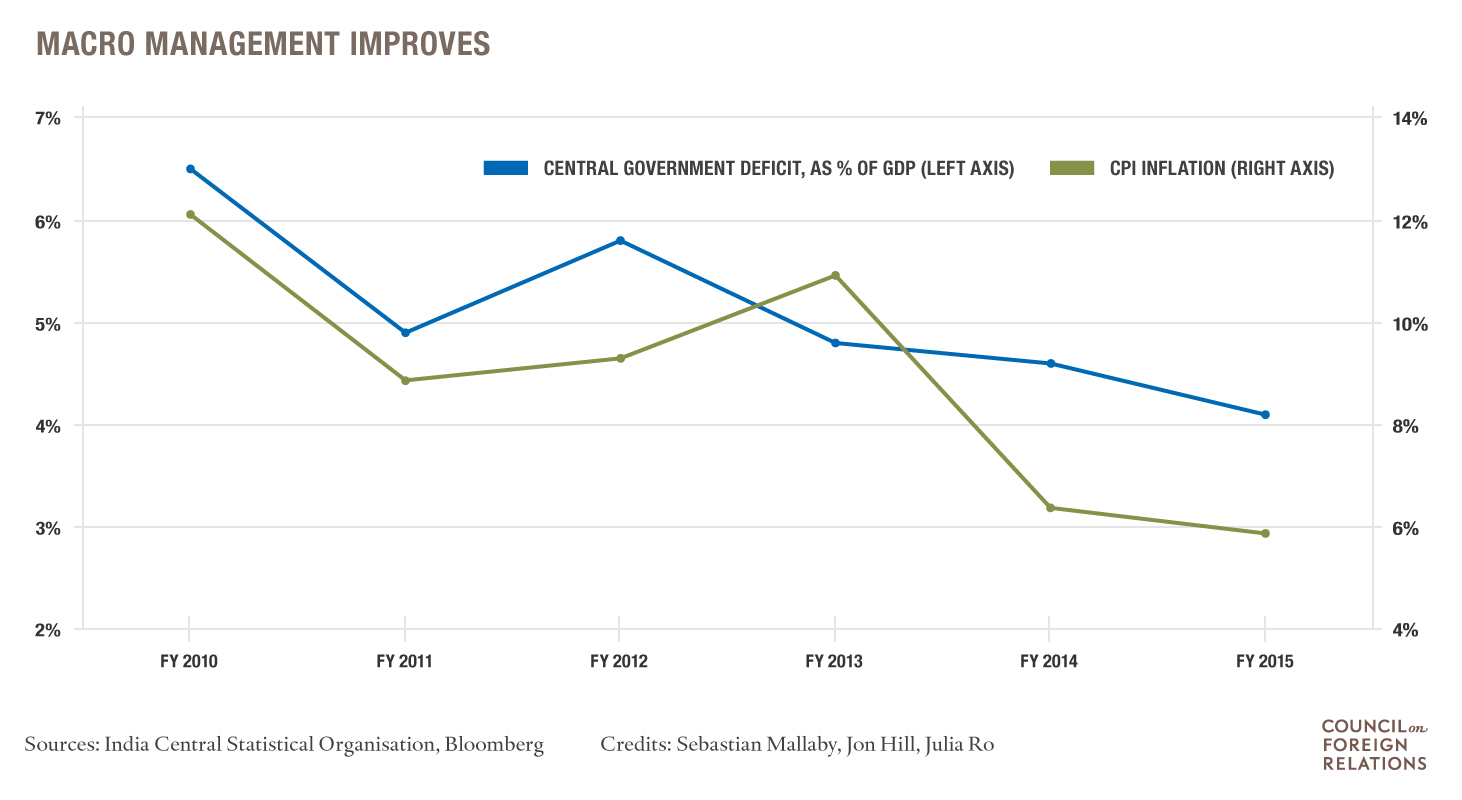

Fiscal Discipline

Skeptics might object that improved macroeconomic management is itself a byproduct of cheap oil. For example, consumer-price inflation has tumbled from an average of over 9 percent in 2011–2013 to less than 6 percent in 2014–2015: presumably cheap commodity prices explain much of this progress? Actually, oil has very little weight in India’s consumer-price index, which is dominated by food and services. Inflation has come down mainly because the central bank has stuck to a tough monetary policy and has committed itself to a formal inflation target.

More on:

A similar verdict applies to India’s budget management, which has also improved lately. Some of the reduction in the central government’s budget deficit, which has fallen from 4.6 percent of GDP in the last fiscal year before Modi took office to about 4 percent now, reflects an automatic windfall from the oil price, which cut the cost of fuel subsidies. But much reflects the government’s determination to raise diesel and gas taxes, seizing the opportunity presented by cheap crude to do so at a time when consumers would not be hurt. Meanwhile, the Modi administration has done well in shifting spending from consumption to investment—an act of political courage that bodes well for future growth.

If the government gets less credit than it deserves from India’s skeptical political classes, why might this be? Part of the answer lies in politics: the Hindu nationalism of Modi’s support base is understandably unpopular with India’s cosmopolitan elite. Another part of the answer is personal: Modi is too arrogant to compromise, too vain to delegate, and is given to peacocking in extravagant outfits that offend the puritan sensibilities of Mahatma Gandhi’s political descendants. But a third source of the skepticism lies in policy failures—failures that relate not to macroeconomic management but to microeconomic good sense.

Cheap Slogans, Lagging Reforms

The prime minister took office in May 2014 as a reformer, promising to cut the red tape and corruption that hold India back. Almost two years later, the results have been disappointing. Modi’s most high-profile reform measure—a tax reform that would sweep away those customs checks that keep trucks idling at state borders—is stuck in the upper chamber of the parliament. Arguably, this is not Modi’s fault, since the upper chamber is controlled by the obstreperous opposition, which is determined to repay Modi’s party for its obstructionism when it was in the minority. But given that the opposition supports the tax reform in principle, it seems likely that the measure could have passed by now if Modi had courted his opponents more assiduously and bought them off with smart concessions. Unfortunately, rather than compromising with his adversaries, Modi prefers to belittle them.

The prime minister has meanwhile failed to deliver other reforms that promise great gains. He is uninterested in privatizing inefficient state-owned companies, even though the proceeds could help to plug the country’s infrastructure gap. He has been unable to muster support for land reform and labor reform, and has been reduced to inviting state governments to take the lead on both counts. In the absence of solid achievements, he has rolled out a series of cheap slogans—“Digital India,” “Skill India,” “Make in India,” and so on. In the words of one exasperated reformer, “When all is said and done, more is said than done.”

There is no doubt that Modi could do better on the microeconomic front. Having spent a dozen years as chief minister of Gujarat, he seems stuck in the mindset of a provincial executive: He is more interested in projects than in policies; he is a modernizer, not a reformer. And yet, all this being said, the glass is not completely empty. Modi has vigorously advanced a program of financial inclusion, resulting in the creation of millions of new bank accounts; coupled with a new biometric national ID system, this will enable the government to make welfare payments to its citizens without a large fraction of the money being siphoned off. Meanwhile, the formula for distributing tax revenues from the center to the states has been made more generous and, just as importantly, less capricious and political. The restriction on foreign direct investment in the insurance sector has been loosened. Maybe, just maybe, that blocked tax reform measure will make it through the upper house of parliament before this year is out.

The Zombie Bank Problem

The remaining source of skepticism on India concerns its lumbering state-owned banks. Rather like China, India responded to the 2008 crisis by pumping up growth with a splurge of corporate lending. Much as in China, some of this money will never be paid back; private estimates suggest 17 percent of loans are “stressed.” Rather than pulling the plug on deadbeat borrowers, banks are drip-feeding them with new loans to cover up the fact that the bankers blundered in lending to them. This nurturing of zombies may come at the expense of financing new ventures that could generate good jobs.

India’s banks are certainly a mess. But their troubles do not look sufficiently serious to hobble growth. Part of the reason is circular. With the economy expanding by more than 7 percent per year, most borrowers will earn enough to pay their creditors: therefore, as a share of the fast-growing economy, bad debts are likely to decline. Moreover, falling inflation has allowed banks to cut the interest that they pay to their depositors while not cutting the rates they charge to their borrowers: Fatter margins will generate the profits needed to provide for bad loans. Besides, India’s authorities are prodding the banks to deal with the bad debt problem. They are shaking up top management and have readied a bankruptcy reform that would make it easier to foreclose.

Indeed, to invert the skeptics’ argument, the fact that India is growing fast despite its banking problems only goes to show how it could accelerate as those problems are addressed. At some point in the future, bank lending will pick up again, both because banks’ balance sheets will strengthen and because companies’ demand for capital will intensify—recently, part of the cause of weak lending has been weak demand for capital, as companies have reckoned with a glut of manufacturing capacity, both in India and worldwide. Add in the fact that foreign portfolio investors withdrew money from India last year, and you have to ask the question: if India can grow at over 7 percent without financial exuberance, what might happen when the financial cycle turns?

The bottom line is that India’s potential is enormous. Its population is young and dynamic: It boasts 234 million citizens between the age of fifteen and twenty-four, compared with 190 million in China. With a per capita GDP less than half of China’s, moreover, India has far more scope for catch-up growth. And for now, at least, India’s macroeconomic management is credible; its microeconomic record displays some forward momentum. With this year’s oil prices unlikely to rise much above last year’s average of $50 per barrel, India’s performance in 2016 should, at a minimum, match 2015. If cheap oil is bolstered by better monsoons, and if the financial cycle turns favorable, the world’s largest democracy could take off.

* For more on India’s economic challenges, read Restart: The Last Chance for the Indian Economy by Mihir S. Sharma.

Online Store

Online Store